Evidence from real-world data (RWD) can be used to complement and contextualize clinical-trial evidence that is appraised during health technology assessments (HTA). With the use of RWD in such use-cases, there come additional study design and analytical considerations whose purpose is to ensure that the desired knowledge is extracted from RWD. One such study-design consideration is whether or not to use RWD that were collected in the same period as the clinical-trial data.

Let’s take a journey through how this calendar-time consideration played out in a HTA-related comparative-effectiveness study in the fictional country of Zamunda.

The road to market-access of vidumab¹ in Zamunda

Imagine this — Eland Pharma2 just announced that the results of their phase 3 trial for vidumab are promising: vidumab has been shown to significantly improve the survival of melanoma patients in comparison to conventional chemotherapy. Additionally, the safety profile of vidumab is deemed impressive by melanoma experts. By drug-development standards, vidumab is shaping up to be a slam dunk for Eland pharma.

Indeed so: After submissions and discussions with the Zamundan Drug Regulatory Agency, Eland pharma was granted market authorization for vidumab. The only hurdle before getting vidumab on the formulary was a health technology assessment (HTA). While Eland Pharma recognized HTA as an additional hurdle, they felt confident in their clinical-trial data given they had already proven the safety and efficacy of vidumab to the regulatory agency. What could possibly go wrong?

After a 90-day evaluation period, the Zamundan HTA body reported that it had failed to reach a conclusion as to whether to include vidumab within the country’s cancer formulary. The HTA body stated that it could not reach a definitive conclusion regarding the cost-effectiveness of vidumab, the reason being that while conventional chemotherapy was the control arm in the phase 3 trial, that was not the standard-of-care in Zamunda for patients with melanoma.

For Eland Pharma, this equivocal verdict felt somewhat like a defeat. Fortunately, the defeat was only partial as the company was given an opportunity to submit additional evidence to highlight the comparative effectiveness of vidumab to luzumab1, which was the standard-of-care for melanoma patients in Zamunda. While the opportunity to submit additional evidence was great news, the immediate challenge that came with the prospect of submitting additional evidence was the absence of studies that directly compared vidumab to luzumab.

It became crystal clear to Eland Pharma that a robust observational study design was their best, if not their only, chance at getting melanoma patients access to vidumab.

After some internal deliberation, Eland Pharma decided to perform a comparison of vidumab to luzumab using vidumab-trial data and luzumab data collected via electronic-health records (EHR). Luzumab had been on the market for at least 6 years, so there was likely ample data on exposure to luzumab, among melanoma patients, in the real-world.

Moreover, Eland Pharma felt the richness in EHR data would enable them to identify a real-world cohort that aligned with the clinical-trial cohort, as much as possible, in terms of demographics, tumor types, genomic markers, histology, disease severity and treatment history.

Beyond these characteristics, one important study-design consideration that the company had to contend with was that of the temporality of EHR-derived data to that of the clinical-trial data. That is, Eland Pharma had to decide whether the time period that they used to create a cohort of patients who received luzumab should be contemporaneous with the clinical-trial period for vidumab.

Contemporaneous vs non-contemporaneous cohort?

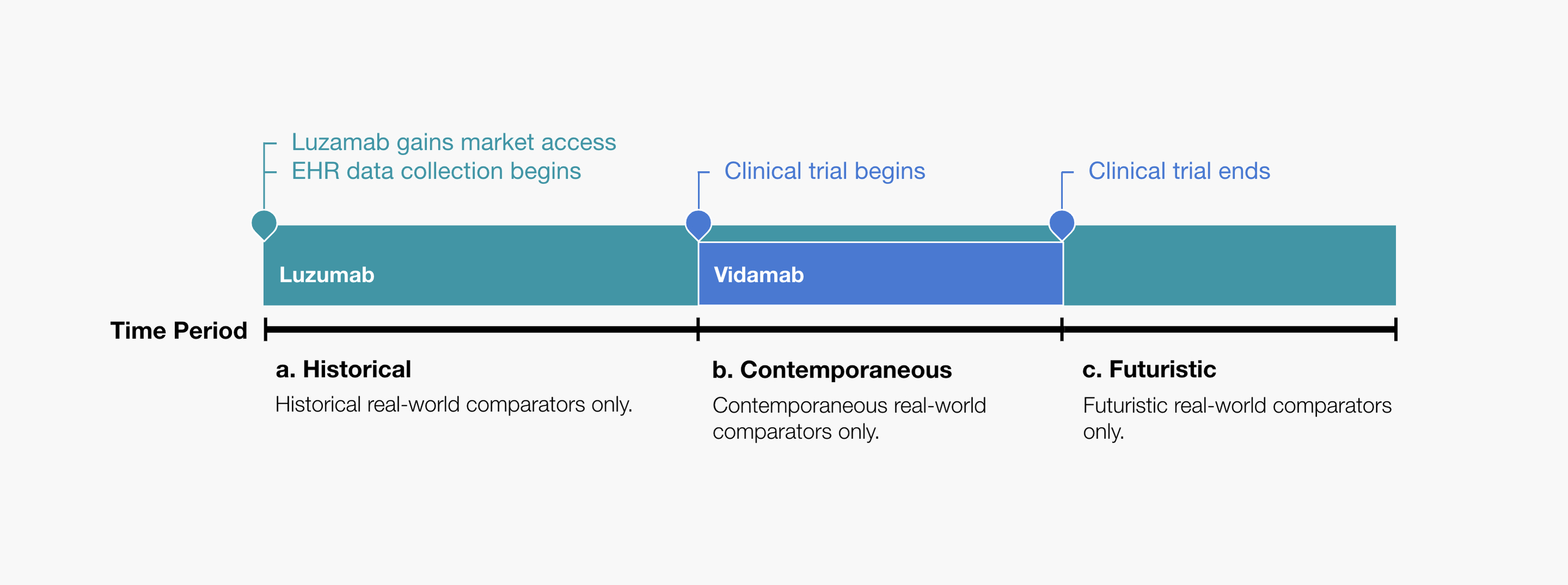

With the EHR data available in Zamunda, it was possible for Eland pharma to construct a real-world comparator group that was either historical, contemporaneous or futuristic, in calendar time, relative to the trial-based vidumab arm. The pharmacoepidemiology team illustrated the possibilities as shown in Figure 1, where (a) contains the historical control, (b) contains the contemporaneous control, and (c) contains the futuristic control.

Figure 1. Eland Pharma illustrates the possibilities of using a real-world comparator group: a) Contains historical real-world controls only. b) Contains contemporaneous real-world controls only. c) Contains futuristic real-world controls only.

While there were many study design elements to consider with these possibilities, the pharmacoepidemiology team recommended that the supplemental comparative-effectiveness analysis only include the contemporaneous comparator group. The team’s decision was driven by the consideration of the possibility of confounding3 being introduced to the analysis due to temporal changes in treatment guidelines, available treatments, diagnostic procedures, etc.4

Specifically, the team wanted to reduce the possibility of the observed treatment effect being explained by calendar-time changes rather than the true relative efficacy of the treatments. That said, the team was cognizant that the decision to use a contemporaneous versus a non-contemporaneous cohort is a highly nuanced one, with decisions being made on a case-by-case basis, while taking account of factors such as sample size, clinical practice changes, etc.

If contemporaneous EHR data were insufficient in sample size, it would then be reasonable for them to consider including luzumab data that were collected before and after the clinical-trial period. The inclusion of non-contemporaneous data would also be reasonable if changes in patient-care practices had been minimal over time.

After executing an observational study-design that was deliberate in recognizing and minimizing errors due to chance, selection bias, confounding and measurement error, Eland Pharma was able to show that there was evidence that their drug, vidumab, was likely more effective at treating melanoma than the current standard of care, luzumab.

The HTA body considered this additional evidence to be compelling, granted the drug market access in Zamunda, and included the drug in the formulary for melanoma patients. This decision was welcomed by all! As melanoma patients began receiving the much awaited vidumab, teams at Eland Pharma popped champagne to celebrate a job-well done — “Oh, what you can accomplish with EHR data,” one pharmacoepidemiologist mused.

References

-

Fictional oncology product

-

Fictional pharmaceutical company

-

Common example of confounding: A spurious association between owning a cigarette lighter and the odds of getting lung cancer. The observed association is driven by the fact that smokers are more likely than non-smokers to own a cigarette lighter, and smokers are more likely than non-smokers to develop lung cancer.

-

"Real‐world evidence to support regulatory decision‐making for ...." 11 Mar. 2020, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/pds.4975. Accessed 9 Jun. 2021.